Above is the Halloween radio adaptation of the War of the Worlds by WKBW in Buffalo. WKBW originally broadcasted War of the Worlds in 1968 and updated versions throughout the 1970’s. For myself, it was a Halloween tradition to sit on the front steps, chow down some Halloween candy, and listen to the broadcast. Although the program would start at 11 PM, I had no worries, as going to a Catholic school, the following morning was All Saints Day and that meant an off day. It wasn’t only Western New Yorkers who listened to the dramatization of their city being destroyed by Martians, WKBW’s 50,000 watt transmitter would reach as far into the Carolinas once the Sun set.

The 1968 broadcast was an homage to Orson Wells legendary 1938 radio version. The events were transplanted to the Buffalo region. In 1968, KB DJ Danny Neaverth opens up the proceedings with a brief introduction. If you lived in Buffalo during that era, Neaverth’s presence around town seemed ubiquitous. I can remember watching Neaverth’s noon weather report on WKBW-TV, hearing him at an evening’s Braves game handling the PA duties (two for McAdoo!), then being woken up by Neaverth’s morning show at 6 AM so I could deliver the Courier-Express.

The 1971 version has an updated introduction by Jeff Kaye. That intro describes various events caused by the 1968 program. Much like the myth of the 1938 panic, there is some hyperbole involved. The local newspapers did not report anything unusual the following day except for a few calls made into the station. After the intro, the broadcast commences with the real newscast from that day. The first sign of something different is when the news ends with a report from Mt. Palomar Observatory that nuclear sized explosions had been observed on Mars.

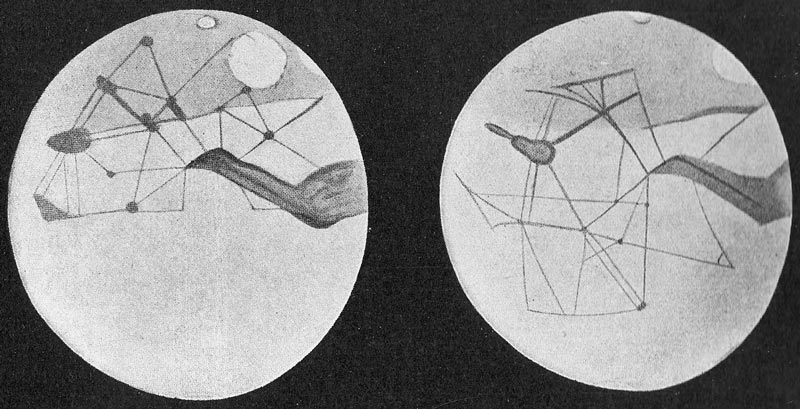

The real director of the Mt. Palomar Observatory at the time was Horace Babcock (the broadcast used the name Benjamin Spencer). In 1953, Babcock first proposed the use of adaptive optics to reduce atmospheric interference for astronomical imaging. This technique, which utilizes a laser created guide star and deformable mirrors in a telescope’s instrument package, is standard on all modern observatories. From 1947-93, Mt. Palomar was the largest telescope in the world.

Were the nuclear sized explosions on Mars a realistic plot point? At first glance that might not seem to be the case. However, keep in mind the Martians made it to Earth in a 24-48 hour period. Standard chemical rockets take about 8-10 months to complete a voyage to Mars. What could have propelled the Martians so fast to Earth? One possibility is nuclear pulse propulsion. The concept is targeted nuclear explosions are used to provide impulse to spacecraft. From 1958-63, Project Orion worked on such a propulsion method. Eventually, the project was shut down by the Nuclear Test Ban Treaty which, obviously, would not apply to invading Martians.

To be fair, the folks at WKBW were concerned with providing programming that had a Halloween ambiance rather than scientific rigor. And they accomplished this by letting the invasion gradually slide into the program. It is 20 minutes in until the invasion occupies the show completely. During that first 20 minutes, listeners are treated to a time capsule of 1968 radio. The news of the day opens with the Vietnam War and ongoing peace talks (the 1971 version also would open with news from Vietnam, which gives you an idea how well those talks went), Governor Rockefellar breaking ground on the new UB Amherst campus, and various local police busts. The video removed the music interludes for copyright purposes. Ads include an 8-track stereo player for $49.95 ($345 today) and shoes for $13.00 ($90 today). The broadcast takes a dramatic turn with the announcement of a meteor strike on Grand Island.

When that announcement was made, it could be heard throughout the East Coast. WKBW transmitted with a 50,000 watt tower, the maximum allowed for AM stations. At night, the range of AM stations expand greatly. I can remember listening to Sabre-Bruins hockey games and switching back and forth between the Buffalo and Boston broadcasts. Also, I have tuned into St. Louis’ KMOX in both Buffalo and Houston during the late 70’s when Bob Costas worked there. While FM has advantages in sound quality over AM, it cannot match the range of AM radio. And that is due to the nature of the Earth’s ionosphere.

During the day, ultraviolet and x-ray radiation strike atoms in the upper atmosphere. This energy ejects electrons, which carry a negative electric charge and forms the various ionosphere layers. During the day, the lower D and E layers absorb AM radio waves. Here, the atmosphere is still thick enough so electrons that absorb radio waves collide into air molecules dampening the radio signal. At night, these lower layers dissipate as there is no sunlight to continue the ionization process. This leaves radio waves free to reflect off the higher F ionosphere layer. Here, the atmosphere is tenuous enough so collisions with air molecules are rare. As a result, AM radio waves are reflected back to the ground enhancing the station’s range. FM stations do not enjoy this effect as their transmissions are at shorter wavelengths, reducing the collision rate with free ions in the F layer.

For those who heard the original broadcast outside of the Buffalo area, and those listening to it now, here is a map to give you a framework of the events:

Nominally a sleepy rural area outside of Buffalo, Grand Island has had an interesting history. Navy Island, adjacent to NW Grand Island, was once considered a potential site for the United Nations. In 1825, a city on the island called Ararat was proposed as a site for Jewish refugees which never came to fruition. The Niagara River current, as mentioned in the broadcast, is swift at 3 feet per second and would pull anyone trying to swim across away and over the Falls eventually. That, of course, happens when the Grand Island bridges are blown in a vain attempt to trap the Martians on the island.

Nominally a sleepy rural area outside of Buffalo, Grand Island has had an interesting history. Navy Island, adjacent to NW Grand Island, was once considered a potential site for the United Nations. In 1825, a city on the island called Ararat was proposed as a site for Jewish refugees which never came to fruition. The Niagara River current, as mentioned in the broadcast, is swift at 3 feet per second and would pull anyone trying to swim across away and over the Falls eventually. That, of course, happens when the Grand Island bridges are blown in a vain attempt to trap the Martians on the island.

The invading Martians make their way downtown to Niagara Square where Irv Weinstein is stationed atop City Hall. Weinstein started on the radio side of WKBW in the late 50’s, moving over to television in the mid 60’s. For the next next three decades, Weinstein was the most prominent news figure in the Buffalo area. Weinstein did refrain from using his trademark “pistol packing punks” (heat ray packing punks?) in the War of the Worlds. I do not know if there was actually a communications center on top of City Hall back then, but there is an observation platform. You can see Niagara Falls from up there, and on the clearest of clear days, the CN Tower in Toronto.

The dramatization concludes where it began, at the WKBW radio station which was at 1430 Main St. a block north of Utica St. The voice of the last surviving news reporter belongs to Jeff Kaye. You may find that voice familiar. During the 1980’s, Jeff Kaye did an admirable job filling the large shoes of John Facenda at NFL Films. Kaye also produced the War of the Worlds broadcast. After the Martian’s poison gas takes out the last of the WKBW team, Dan Neaverth returns to conclude the broadcast noting that H.G. Wells ended the War of the Worlds with the Martians dying off, unable to resist Earth’s microbes. Wrote Wells:

“But there are no bacteria in Mars, and directly these invaders arrived, directly they drank and fed, our microscopic allies began to work their overthrow. Already when I watched them (the Martians) they were irrevocably doomed, dying and rotting even as they went to and fro.”

And more than likely, Wells was right about the lack of microbes on Mars, at least on the surface anyway. Unlike Earth, Mars does not have an ozone layer to block out ultraviolet radiation from the Sun. Also, Mars lacks a magnetic field. The Earth’s magnetic field shields life from harmful cosmic rays Unabated, this radiation is highly harmful to any life on the Martian surface, whether it be microbes or astronauts in the future. However, the subsurface of Mars may be another story.

One of the key discoveries on Mars the past few decades has been the existence of water below the surface. On the surface, the lack of atmospheric pressure reduces the boiling point of water so that if it does not freeze it will evaporate quickly. However, the subsurface of Mars has been found to have significant amounts of water. Planning for future human exploration of Mars entails utilizing this water for long duration stays on the red planet. Moreover, where there is water, there may be life. And this leads to the issue of planetary protection.

NASA has an Office of Planetary Protection. The goal is to prevent Earth microbes from contaminating Mars and vise versa. This will become a growing concern for the space program when attempts are made to land humans on Mars or if a Mars sample return mission is sent. Drilling for water on Mars may expose an ancient subsurface biosphere, and certainly humans could carry Earth microbes to Mars. While the risks involved are still a matter of scientific debate, Wells was very prescient to include this factor in the War of the Worlds.

Regardless of what we discover about Mars in the next few decades, there was a deeper lesson in the original novel that tends to get lost in modern versions. The WKBW broadcast capped a night of Halloween themed programming and the primary goal was, as Orson Wells said to conclude his 1938 version, “Dressing up in a sheet, jumping out of a bush and saying, ‘Boo!”. H.G Wells had intended War of the Worlds as a critique of colonialism. Wells makes this clear on page three of the novel:

“And before we judge of them (Martians) too harshly we must remember what ruthless and utter destruction our own species has wrought, not only upon animals, such as the vanished bison and the dodo, but upon its inferior races. The Tasmanians, in spite of their human likeness, were entirely swept out of existence in a war of extermination waged by European immigrants, in the space of fifty years. Are we such apostles of mercy as to complain if the Martians warred in the same spirit?”

At the close of WKBW’s The War of the Worlds, Dan Neaverth asks the audience to think about what they would have done if the invasion was real. An equally important question to ask is what you would do if you were on the invading side. Would you join the invasion as the social forces of war coalesced around you, or would you resist the tide, as Bertrand Russell did in World War I:

“I knew it was my business to protest, however futile that protest might be. I felt that for the honour of human nature those who were not swept off their feet should show that they stood firm.”

Think about it.